Eilean Munde, Sacred Burial Island, Loch Leven

On the death of a Highlander, the corps being stretched on a Funeral board, and covered with a coarse linnen wrapper, the friends lay on the breast of the deceased a wooden platter, containing a small quantity of salt and earth, separate and unmixed; the earth, an emblem of the corruptible body; the salt, an emblem of the immortal spirit.

All fire is extinguished where a corps is kept; and it is reckoned so ominous for a dog or cat to pass over it, that the poor animal is killed without mercy.

Thomas Pennant: A Tour in Scotland. White, London; 1776

With thanks to the National Trust for Scotland

© Canna House Photographic Collection

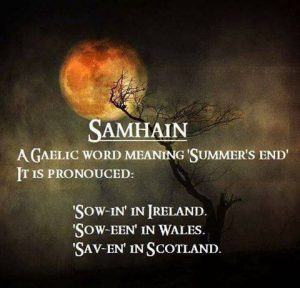

The name Halloween comes from a Scottish shortening of All-Hallows Eve and has its roots in the Gaelic festival of Samhain.

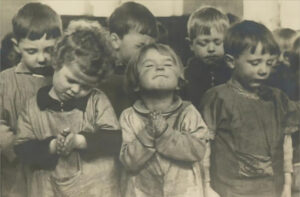

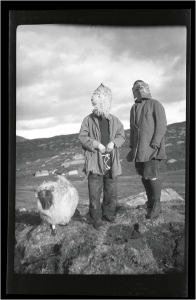

Scottish Halloween traditions have certainly changed over the years. In the 1930s on South Uist, children were known to make homemade costumes from the skin and skulls of dead animals.

The otherworldly magic of a traditional Hebridean Halloween was captured on camera by Margaret Fay Shaw, who amassed a huge collection of Gaelic song, poetry and images when she lived in the west of Scotland from the 1930s onwards.

A Hebridean Halloween: Play here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zIdS42vADis&feature=youtu.be

Margaret and her husband, Gaelic scholar John Lorne Campbell, bought the Isle of Canna in 1938, donating it to the Trust in 1981. Their collection, archived at Canna House, includes images and film of Halloween, or Samhain, festivities in South Uist.

The roots of Halloween in Scotland go back to the Gaelic festival of Samhain. ‘There are lots of theories about the origins of Samhain, but the overriding idea is that it was a time when the boundary between this world and the other world could be crossed,’ says Canna House archivist and manager Fiona Mackenzie.

“That was the origin of dressing up – you were disguising yourself from the spirits and trying to please them, so they’d look after you during winter. ”

Fiona Mackenzie

‘Costumes were usually made out of sheepskin or whatever was lying around the croft. Unravelled rope was used to make headpieces. In Margaret’s photos you can see someone dressed entirely in sheepskin. She wrote in the 1930s about watching a boy skin the head of a sheep, leaving the ears intact. He lifted it over his head and looked just like a sheep,’ continues Fiona.

Traditional Samhain costumes © Canna House Photographic Collection

Fiona adds: ‘There’s a lot of food involved in Samhain too, both as a feast day for yourself but also to leave food out for the spirits.’ One tradition was to leave a place set at the table to welcome the souls of dead relatives.

Food for Halloween (the word comes from the Scots shortening of All Hallows Eve) included a pudding shared by the family, with a silver sixpence, a thimble and a button hidden inside. There were also traditions to do with romance. You could foretell the future of two sweethearts by throwing two nuts into the fire. If they exploded at the same time, it was said ‘they were away together’.

The Massed Pipes and Drums of the Scottish and Irish Regiments led the procession of the Queen’s Coffin and Gun Carriage through the streets of London.

The Massed Pipes and Drums chose to lead off from the Funeral at Westminster Abbey with ” Chi Mi Na Morbheanna”.

Chì mi na mòrbheanna (commonly known in English as The Mist Covered Mountains of Home) is a Scottish Gaelic song that was written in 1856 by Highlander John Cameron (Iain Camshroin), a native of Ballachulish and known locally in the Gaelic fashion as Iain Rob and Iain Òg Ruaidh. He worked in the slate quarries before moving to Glasgow where he was engaged as a ship’s broker. He became the Bard of the Glasgow Ossianic Society and also Bard to Clan Cameron.

He returned to carry on a merchant’s business along with his elder brother and to cultivate a small croft at Taigh a’ Phuirt, Glencoe, in his beloved Highlands. Other songs and odes appeared in The Oban Times and in various song books. He was buried in St. Munda’s Isle in Loch Leven. Wreaths of oak leaves and ivy covered the bier. The song is a longing for home and, with its wistful, calming melody and traditional ballad rhythms, is often used as a lullaby.

See: The Massed Pipes and Drums of the Scottish and Irish Regiments

A snuff mull is a variation of a snuff box, used for the consumption of tobacco in its powdered form.

The ritual that accompanied this became established around the 1600s, as snuff became popular in Britain. These can be found in many forms, a popular type being the ‘pocket snuff mull’.

Snuff mulls were especially popular in Scotland, with the name seemingly deriving from ‘snuff mill’.

Snuff mulls were made from the 1600s to the 19th century, with little change to their style or design during this time.

These were made from various resources, including silver mounted horn, sea shells, rock crystal and other semi-precious materials indigenous to Scotland.

The Royal Company of Archers and their white and green cockades (not Hanoverian black) in their bonnets, it is indeed an interesting story and one with strong Jacobite connections. The official line is that the company was formed in 1676 to be the King’s body guard in Scotland, though some claim their origins date back to James VI. Then, as now, it was an elite group of men.

They adopted the tartan uniform – which is often seen in discussions about late 17th and early 18th century tartans. They were led by a number of well known Jacobites, including James Fifth Earl of Wemyss, at the time of the ’45. After the ’45, they were regarded with great suspicion, so when George IV famously came to Edinburgh in 1822, the company adopted a uniform (still bearing odd throw-backs to previous centuries) of the Government tartan, also known as the Black Watch.

As the historian for the company wrote in 1875: ‘The spirits of the old Jacobite members might well have stood aghast, if they could have beheld their successors guarding into Edinburgh the carriage of a King of the house of Brunswick [ie Hanover].’

From the middle of the 19th century, the current uniform was adopted and worn, fairly unchanged ever since. It features a hardened bonnet (similar to those worn in the Highland Revival) in dark green, the feather, and a white and green cockade.

Ref: the National War Museum, the Royal Company of Archers.