Images of the Highland Clearances

Lochaber No More– John Watson Nicols 1863

‘Lochaber No More’ depicts a scene from the time of the Highland Clearances, an infamous and bitter period in Scottish history during which an estimated 200,000 inhabitants were forced from their land between the 1770s and 1850s. The root causes were complex, but include overpopulation, near starvation due to poor harvests, severely raised rents by exploitative landlords, the introduction of widespread sheep grazing and the reluctance to abandon old farming methods, all aided and abetted by the extravagant promises of unscrupulous emigration agents.

It was an outflow of the poorest and most vulnerable. Nicol treats the subject with a high level of emotional intensity. A man and a woman are aboard ship, bound for a new life in North America, Australia or New Zealand. She weeps inconsolably, while he gazes back wistfully at their homeland. The meagre belongings at their feet, notably their frail dog, poignantly evoke their desperate position. The title stems from both a traditional lament favoured by departing emigrants and a song by Scottish poet Allan Ramsay – father of the famous portrait painter of the same name – which tells of an enlisted Highlander’s nostalgia for his home country.

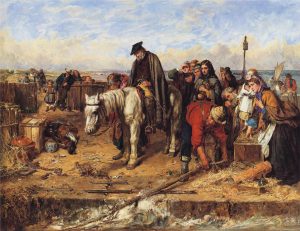

The Last of the Clan – Thomas Faed 1883

Also inspired by the Highland Clearances which forced many to emigrate in search of a living, this painting shows the quayside of a Highland or island village, with a group of figures watching the departure of an emigrant ship for the colonies.

‘When the steamer had slowly backed out, and John MacAlpine had thrown off the hawser [rope], we began to feel that our once powerful clan was now represented by a feeble old man and his granddaughter, who, together with some outlying kith-and-kin, myself among the number, owned not a single blade of grass in the glen that was once all our own.‘ Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1865, this painting was accompanied in the catalogue by this paragraph which was probably written by the artist himself.

Such emigrant scenes were common occurrences in mid 19th-century Scotland when, partly as a result of the Highland Clearances, the land could no longer support the people. Emigration, often forced, to places such as America and Canada, was the only hope of survival. Though sometimes, as depicted here, the very young, women and the old were not allowed to go, and only able-bodied men sailed to the colonies in the first instance. A masterpiece of genre painting on a relatively large scale, Faed combines an eye for detail with a fluent painterly manner. The high quality of the still life painting of objects strewn on the quayside – a ginger jar, a pheasant, pots and packing cases – and the costumes worn by the figures, are typical of Faed at his best. These elements are set amidst a fine landscape with a breezy sky and distant choppy sea. All in all, Faed brings an epic quality to a subject which is charged with tragic emotion and powerful immediacy.

A contrasting story and image.

The Emigrants – William Allsworth 1844

This work by the English artist William Allsworth became known as the definitive depiction of nineteenth-century Scottish emigration to New Zealand thanks largely to its publication as a lithograph by Day & Haghe in London around 1855. It shows a prosperous Scottish family in a Highland landscape, surrounded by their worldly goods — piles of luggage, animals, cases of trees and plants and farm implements. Clearly, they are emigrating, with everything needed for successful colonial life.

Their destination is signalled by the ship anchored just offshore. Close inspection reveals that it is flying the 1835 New Zealand flag. The family’s Scottishness is loudly proclaimed by the wearing of tartan: they are the Mackays, gathered near their ancestral home in Sutherlandshire, and it is their chartered ship, the Slains Castle, that rides at anchor in the background.

But not everything in the painting is as it seems. A family named Mackay did arrive at Nelson on the Slains Castle in January 1845, but recent research by descendants has revealed that their real name was Mackie, and that their father, James, was not the brother of a Sutherlandshire laird he claimed to be, but the second son of a merchant in Aberdeen. Furthermore, he had spent most of his life in London, where he worked as a banker. He married an English woman and the children were all London born. And the Slains Castle was not chartered by the family — nor did it sail from Scotland. It was a New Zealand Company ship that sailed from Plymouth in October 1844 with several other passengers besides the ‘Mackays’.

It is possible that James Mackie embellished his family history because emigration to such a distant destination as New Zealand gave him the opportunity to make a new start with a fabricated noble identity.

Other assorted but relevant images:

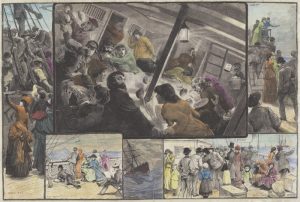

James Fagan-The Emigrants Farewell. The Lord be with You 1853. Lithograph

Charles Joseph Staniland- Emigrants Going to Australia, London 1880s

Oh Why, I Left my Hame? Thomas Faed 1886